Human history has always been turbulent and is mired with conflicts and violence. Different interests in land, power, religions, politics, etc have created situations, some of which still enduring today, which have harmed individuals and groups of people. Humanity always endeavours to learn from its past mistakes. However, the unfortunate reality is that even today we see new conflicts, or old ones flaring up, which we liked to have avoided.

We acknowledge that truth, and a honest history, is a very important necessity to confront our demons and resolve past, present and future issues.

Different types of guilt

Many Germans felt a ‘collective guilt’ (Kollektivschuld) upon the end of World War II. Including those who (said) not to have participated in the atrocities. This guilt existed because they knew right from wrong and felt guilty for the actions of their family members and neighbours, as well as their inaction to try to stop the many horrors and wrongs. Those that were active in WWII sometimes proclaimed to be remorseful while under control of the allies, it is hard to establish sincerity in these matters. In most cases time will tell. Over the decades and generations this collective guilt did change many attitudes and today most Germans depolore their legacy. Unfortunately there are some who still revert to past opinions with regards to foreigners, religion and/or racial differences.

The Netherlands was an occupied country during WWII. As such it was liberated and quickly wrongs were righted. However, the Netherlands had over a hundred thousand of NSB (Fascist, Nazi) members, many of whom were active in the war. Although the liberated Netherlands did prosecute many and did address its collective guilt, the primordial attitudes towards those different and some foreigners are still part of today’s Dutch society. On the other hand also the Netherlands has new generations with more enlightened morals and attitudes.

Previous dictatorships in for example South America have been looking to resolve their guilt. Initially they followed the Spanish model Pact/Law of ‘Forgetting’. The idea behind it was to walk away from the past, forget it, and look towards a positive future where everyone can work together towards a more positive future. However, over the years most of these countries have repealed any such laws and agreements and come to the realisation that past wrongs can’t just be forgotten.

While many other countries stopped these laws, in present day Spain’s ‘Forgetting’ is still in place. Currently many, correctly, argue that Forgetting was a good ploy by the guilty to avoid answering for their crimes. Although Forgetting assisted in the 70’s with a transition to a democracy it did not help all those who suffered, and continue to suffer. Only when most people can forgive each other on an individual basis can we see a successful ‘national reconciliation’. The responsibilities and guilt for the repression during and following the Spanish civil war/coup have to date not fully been addressed. Not only are many victims left with physical and emotional scars but by suppressing the painful memories it seems that the country/population has not fully learned from its past. In fact, Spain still has many Franco aficionados celebrating him and the era. Spain is still not fully acknowledging its violent past in an open and honest way. This excellent documentary will explain more and why it is important to address this.

What can we learn?

We can learn from this. Rather than forgetting, ignoring, moving on, we do need to address past wrongs. We need to look for real national reconciliation where people can emotionally move on and perhaps forgive. Only then can we learn from past mistakes, only then can we build a different and more positive future ‘together’.

Our mistakes and crimes.

The House of Habsburg has not been immune to past mistakes and wrong government. Unlike the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, the House of Habsburg has not been in political control of people or lands for the last 400 years or so. Therefore we are in a situation where we may have no apologies for recent history to make. Still, as descendants we feel historical guilt where it comes to certain events prior to 1578. The influence of some of which can still be felt today.

The actions of Charles V, and Juan (John, Jerome, Johannes) under Felipe II were sometimes harsh and according to present day values immoral and crimes. It is clear that the influence of Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros had a profound negative impact on the Catholic church and the Spanish kingdoms. Upon him becoming confessor to Queen Isabella we see amongst others the intensified Spanish Inquisition, the issue of the Edict of Expulsion of the Spanish Jews, and oppression and forced conversion of the Moriscos. The House of Habsburg came into play in 1506/1516 until 1578 and today we can’t rectify past wrongs by itself. However, we do want to acknowledge the suffering of peoples and individuals. We welcome to meet with anyone wishing to do so and declaring that we all have learned from history. We will support any individual, group or government in recognising past wrongs and any governmental programs of recognition, reconciliation and/or compensations.

Expulsion of Sephardic Jews

Preamble

The Edict of Expulsion, also called the Alhambra Decree , issued on 31 March 1492, ordered the expulsion of Jews. They were seen as a threat to the Christian faith. Already since the religious persecution and pogroms as of 1391 half of Spain’s Jews had converted. As a result over 200,000 Jews converted to Catholicism and an estimated 40,000 to 100,000 were expelled.

By 1506 most had left or converted. Sometimes converted in name only. Charles V and Felipe II did not stop the Edict or its practise. Through the Spanish Inquisition those who converted were often challenged and the Spanish Inquisition became a tool of further persecution.

The House of Habsburg apologises and asks forgiveness for the religious and violent oppression of Spanish/Sephardic Jews.

In the 19th century jews could return to Spain and open synagogues, but it wasn’t until 1968 that the Edict was revoked following the second Vatican council. It is indeed never too late to correct wrongs. In 1924 Spain granted Spanish citizenship to the entire Sephardic Jewish diaspora. In 2014, the government of Spain in order to “compensate for shameful events in the country’s past.” passed a law allowing dual citizenship to Jewish descendants (abroad).

Conquest of Granada

Preamble

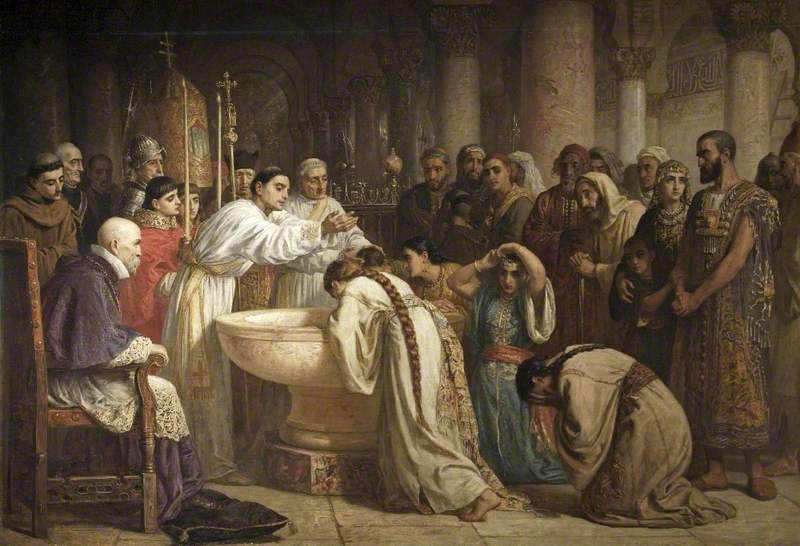

The Muslim population of Granada were under the Treaty of Granada (1491) allowed to stay in their homes and be judged by their own laws. Muslims were not be obliged to convert to Christianity. However, soon after they did come under pressure to convert including forced conversions. This led in 1499 in Granada, Alpujarra and the west of the Kingdom to (small) revolts. These complaints and uprisings were violently put down. In Laujar de Andarax two hundred Muslims were burnt in its mosque. The troubles were used as an excuse to revoke the treaty.

Persecution of the Moriscos

Kings of Aragon were required to swear an oath of coronation to not forcibly convert their Muslim subjects. Shortly after revolts in the 1520s Charles V tried to release himself from the oath. He wrote to Pope Clement VII in 1523 and again in 1524 for dispensation. Initially the request wasn’t granted but in May 1524 a papal brief released Charles V from the oath.

In 1526 Charles V issued edict ordering the expulsion or conversion of remaining Muslims in Aragon. This Edict forbade amongst others the use of Arabic and the wearing of Moorish dress. The Moriscos negotiated this, at a fee, to be suspended for forty years. At this point in time all remaining Moriscos were officially Christian. Mosques were destroyed or turned into churches, children had to be baptised, etc. Moriscos who failed to participate at Mass were punished. Resentment increased.

In 1565 a synod of the bishops of Granada agreed that these soft methods of persuasion should exchanged for repression. Prohibition of all the distinctive Morisco practices: language, clothing, public baths, religious ceremonies, etc. Houses should be inspected for Islamic texts or rites. Sons were to be taken (randsommed) to Castile at the cost of their parents, to be brought up learning Christian customs and forgetting those of their origins. By this time Philip II was the King and in 1567 he gave his approval by Royal Charter (the Pragmatica). After failed negotiations and appeals a small group of the Moriscos took up arms in 1568.

Philip II sent a volunteer army to suppress the region. The volunteers were untrained and not paid but promised rich lootings which they could keep. Pérez de Hita wrote that half of them were “the worst scoundrels in the world, motivated only by the desire to steal, sack and destroy”. Moriscos took their revenge on Christians and priests. Christian houses and churches were set on fire and looted. Both sides sold captives as slaves. The Moriscos sold Christians to merchants from North Africa in exchange for weapons. The Christian soldiers sold captured Moriscos. Mainly surviving women and children which were equally regarded as war booty. The Crown renounced the usual 20% tax on the proceeds. Philip II himself benefitted from the sale of slaves.

The initial small conflict escalated and grew to a full fledged uprising with the Moriscos using guerilla tactics. By 1569 the situation was such that Philip II proclaimed “a war of fire and blood” (una guerra a fuego y a sangre) and instructed his half brother, Juan de Austria, to resolve the uprising.

Juan de Austria leaded an army of about 20,000 men. When Juan de Austria conquered Galera he ordered it to be destroyed as an example. As the Moriscos fought a guerilla style war Juan de Austria decided on a sort of scorched earth response and ordered the destruction of houses and crops. Men were killed and women, children and the elderly were taken prisoner. Records conflict and some say that except for one occasion Juan de Austria gave instructions to respect prisoners and protect the innocents.

In 1571 Juan de Austria won and suppressed the rebellion. The last moriscos fighting were killed in caves where they ended up hiding. After this about half of the Morisco population were expelled from the Kingdom of Granada.

The House of Habsburg apologises and asks forgiveness for the religious and violent oppression of the Moriscos.

Plans were already in place for repopulation. Any properties/land left by the Moriscos was shared out to Christian settlers. Settlers were supported until their land began to bear fruit. Officials were sent to recruit settlers from from western Andalucía, but also from Castile, Valencia and Murcia as far away as Galicia and Asturias and the mountain areas of Burgos and León.

If you think or feel that there are other historical wrongs (prior to 1578) we should mention here please do not hesitate to contact us.